After This Night

In 1983, an 11-year-old girl's taste of independence ends in a lesson she didn't ask for

It’s an evening in autumn. Halloween decorations, tissue ghosts pinned to tree branches, swing in the wind. I savor the look on my father’s face when I tell him I’m going out for a walk — suprise, delight. Most evenings, I’m parked in front of the T.V. “Be careful,” he says.

In the waning light, I take Sterling Street to Berkeley, and Berkeley toward Hampshire. It’s 1983 and I’m eleven. I dabble in independence. Walking alone at night is a distinct pleasure. By myself, there’s no one to calibrate my behavior to. I can be whoever I am becoming. Outdoors, in semi-darkness, possibility carries me.

Our neighborhood expands in the cool air. The big old houses, protected by shingles and double sashes in daylight, become dioramas lit from within. I see parents returning home from work, families eating together, someone on the couch watching Jeopardy. Between the beam of one streetlight and the next, I am a gray shadow, nimble and slight, barely crunching the dry leaves under my feet. After this night, I will be older than I am right now.

It’s 1983 and I’m eleven. I dabble in independence. Walking alone at night is a distinct pleasure. By myself, there’s no one to calibrate my behavior to. I can be whoever I am becoming. Outdoors, in semi-darkness, possibility carries me.

Kelly is coming over. We have agreed to meet in the middle, by Dawn’s house, a half-mile away. Tall, quiet, and shy — unlike me — Kelly harbors some mystery. Whenever she’s embarrassed, the lower half of her cheeks start to flush like an electric burner coming on. Hampshire bends and I reach the fork by Dawn’s house. Kelly’s not here yet so I walk a little further up the road to meet her coming down the hill. Then it occurs to me that she might approach from another direction as several roads converge here.

When I head back down the hill, I notice a person who wasn’t there before, a man. He’s old enough to seem safe; it’s kids I don’t trust, especially teenagers. I would never want to run into a group of teens alone.

He’s standing in the driveway of a large house across the street from Dawn’s. I assume he lives there. Maybe he has come outside to smoke or walk a dog. He turns and calls to me.

“Do you know who lives here?” he says, and he points to the house.

It’s not his home after all. But where did he come from? I notice the driveway looks wider than a typical driveway, more like a parking lot. Maybe it’s not a house. It’s hard to tell.

“No, I don’t know who lives there,” I say. I walk in his direction because the question has drawn me in. Maybe he’s noticed something wrong at the house. Maybe he needs to tell something to the people who live there. I’m nosy. I like talking to people. “Why do you ask?”

As I get closer, I notice that he’s looking down, doing something with his hands, carefully taking something out of his front pocket. He has his back curved to the streetlamp and he’s in shadow. I am in the middle of the street, halfway across, heading towards him when he turns and takes a step in my direction. I freeze.

“Have you ever seen one of these?” he says and he shows me his penis.

I don’t see the penis so much as sense it, like a weapon drawn. It puts me on my heels. I have seen one before, in Playgirl magazine, where the men stroke their hairy chests and smolder-gaze at me with Magnum P.I.-style sex appeal. They hold their penises like trophies.

“You’re disgusting!” I say. I hear the anger in my voice, and my lisp. Disssgusssting, the babyish sound of me. I’m ten feet from him, maybe twelve, the fact that I’ve been tricked tripping me up. But it’s not hard to get away.

I want to tell Dad it was nothing, to reassure him, but I’m shaken up. I can’t sort out my feelings. He doesn’t try to draw me out about it. We’ve never talked about sex. I can’t even imagine what words he’d use - he’s too direct to say something like “private parts” without cracking up. The quiet is a relief.

I pivot and run to Dawn’s front door. The woman who answers is not her mother.

“A man just flashed me over there,” I say, and I point across the empty, dark street. She calls my house and then the police.

My father comes. He tells me that Kelly called to say she couldn’t come over. He figured I would just make my way home after she didn’t show.

When I’m done answering the policeman’s questions, we climb into Dad’s little red Corolla, which seems even smaller tonight. He shifts the car into gear, pats my leg, squeezes my hand.

“Are you okay, kiddo?” he says.

“I’m fine.”

I look out the passenger window so I won’t see him looking at me. Something between us has changed. I scowl at my reflection.

“That must have been upsetting,” he says. “I’m glad you ran away.”

Did I really need to run? From a man who held his penis like a small animal? He could’ve grabbed me, he could’ve chased me, but he didn’t. Still, I know running was right. There are people I should not be so open and friendly with, and after this I will be more careful in our neighborhood. The scale of the incident feels embarrassingly minor, even though the change inside me is not.

Our short drive home lasts longer than usual. We cross Prince Street, then Exeter. I want to tell Dad it was nothing, to reassure him, but I’m shaken up. I can’t sort out my feelings. He doesn’t try to draw me out about it. We’ve never talked about sex. I can’t even imagine what words he’d use — he’s too direct to say something like “private parts” without cracking up. The quiet is a relief.

Our lit home glows ahead of us. We drive down to the bottom of the driveway. He pulls the emergency brake, turns the engine off. I can see my brother moving around his room, building something at his work table. My room is dark, the way I left it.

“Well, I’m glad you’re alright,” he says. Then he opens the car door. “Shall we go in?”

Erica Youngren writes fiction and essays about parenting, health, creativity, and suburban life. She holds an MFA from Sarah Lawrence.

Captivating. The writing is so clear and concise and it builds. You feel something is going to happen and then it does. So much food for thought in these words. Dad's love. Smart protagonist. The neighbor. Great piece!!! Thank you for adding this to the How I Learned Collection.

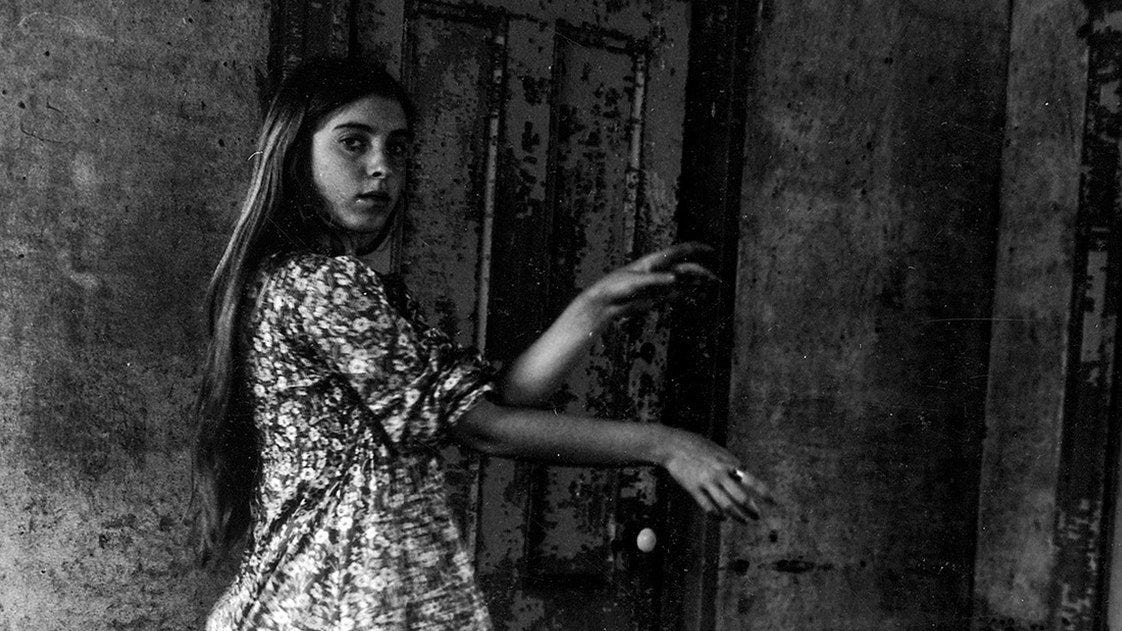

The Woodman photo is perfect - her work is incredible. Great piece. Glad you ran. Glad the dad acted the way he did - so sweet.