There was a sewer under our street. I guess there must have been a sewer under every street, but our sewer was different in that you could actually go inside it. The entrance was just beyond the street that fed into ours. We’d scramble down the hill there, into a kind of ravine. Slanted cement walls led to a cement platform, like a little stage, and that’s where the entrance was, at the back of the platform.

We’d bring flashlights along. You couldn’t go into the sewer without a flashlight; it was pitch dark.

I never told a soul I was doing this. More than once it occurred to me that if I fell and hit my head, I’d rot down there, because no one would know where to find me.

The sewer was round, a perfectly round tube about five feet in diameter and made of cement. A little stream of gooky stuff ran down the middle, so that you had to walk bowlegged to keep from messing up your sneakers. The walls, particularly near the gooky stuff, were covered with a dark slippery substance, most likely algae, which made for treacherous footing. We walked slowly.

People said there were rats down there, but I never saw one. Maybe the rats were frightened by our flashlights, I don’t know, but I still think I would have seen one if they were any to be seen.

Some kids (I just remembered this) wouldn’t go in. They’d wait at the entrance. I wish I could remember who these kids were, but I don’t. Anyway, it’s not hard to guess who they must have been.

No doubt one these kids told his parents about it, which is how the whole thing ended: one set of parents told another, and so on. I don’t remember how my own parents reacted, but it doesn’t really matter, because enough kids got into enough trouble that we couldn’t go down there anymore as a group.

So I started going alone.

I had a crush on Pamela, based in part on the fact that she could throw a baseball farther than me. Sometimes it seemed that she liked me too, but I knew that was impossible.

Our street was a cul-de-sac, a giant C. The main tunnel of the sewer cut straight through the opening of the C, then branched off right and left. As a group we never explored beyond the branching point.

I’d go down there after school. I kept my dad’s flashlight hidden behind some rocks near the entrance so that no one would see me lugging it back and forth.

I never told a soul I was doing this. And more than once it occurred to me that if I fell and hit my head, I’d rot down there, because no one would know where to find me.

I began with the left-hand branch, following it south toward Brian Cohen’s house. Smaller sub-branches, barely big enough to crawl through, fed off this branch every fifty feet or so.

Naturally I found the whole thing terrifying. I’d take a step or two, stop, look back, look forward, take another few steps. Then it’d be too much and I’d have to turn back.

So it must have been a week before I finally reached the end of the north branch and found the note. A wooden board lay across the tunnel, two or more feet off the ground. On the board was a plastic bag; the note was in an envelope in the bag.

I should have said that all the kids who either went into the sewer or stood outside the sewer were boys. I didn’t really play with girls at this age; the girls did their thing, and we did ours, and there wasn’t much overlap. Of course we’d stand in the same line to buy ice cream, things like that, but it was a classic case of girls maturing faster than boys — our only way of talking to them was to say something gross or insulting.

The one exception to the separation rule was Pamela Wilson, who sometimes played sports with us at the insistence of her brother Anthony. I had a crush on Pamela, based in part on the fact that she could throw a baseball farther than me. Sometimes it seemed that she liked me too, but since I knew that was impossible, I decided that she was just being nice because she felt bad about the throwing thing.

I was wrong, though. Her note made this clear. She’d seen me go into the sewer a few times and had decided to leave me this note. She said I had a nice smile.

Actually, that’s as far as I got, the nice smile part. Once I read that, I put the note back in the envelope (the envelope was torn now, but what could I do?) and got the hell out of there.

And that was the last time I ever went into that sewer.

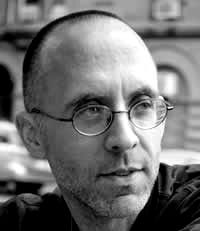

Michael Barrish was a writer and a freelance web developer. He died in 2023 from pneumonia after being diagnosed with a rare and aggressive form of early-onset dementia.

How I Learned occasionally reprints stories that appeared on Michael’s website Oblivio between 1999 and 2020. From Michael’s About page: “Etymology: Oblivio is Latin. Often translated as ‘forgetfulness,’ it suggests a profound lostness, something akin to the English word oblivion, but more oblivious.”

The Oblivio book, published posthumously, is now available on demand. Thank you to Mickle Maher for preserving the work.