The Deep End

When I tell her I met someone at a silent retreat she says, "How does that work?"

I am in the deep end. I’m wearing a flotation belt and my hands are clinging to gallon jugs filled with water that keep me afloat. The steamy, ever-present chlorine-filled air makes me nauseous every time I enter the pool area. The object of this torture is to see if I can be in the deep end, move my legs, stay afloat, and not panic for 30 minutes.

We are several weeks into my weekly private swim lessons.

I am not a toddler, a 6-year-old, or a teen. I am almost 30; this is the farthest I have gotten in any swim class. Sitting deck-side is my peppy, warm, and empathetic teacher, Deb. She is a small, muscular athlete with short black hair, dark eyes, beautiful arms, and a kind smile. She is the athletic director at the Y where my girlfriend swims three times a week. She hires Deb to teach me to swim before we vacation in Mexico.

We are in the shallow end working on the crawl and I start to cry. I feel deep shame about not being able to do something everyone else does effortlessly, especially my girlfriend. Deb and I face each other. Let’s tread water, she says. My salty tears run down my face and into the pool. She tells me how brave I am. She admires me for doing something so risky. She is completely patient and non-judging. When I tell others about it, I say she did therapy with me in the pool.

We have regular lunches and people in public ask if we’re sisters. We laugh and say yes. We don’t look anything alike. Deb’s mother is Choctaw. She has her Mom’s wide face and cheeks and golden skin. I’m a pale Eastern European Jew with green eyes and occasional acne.

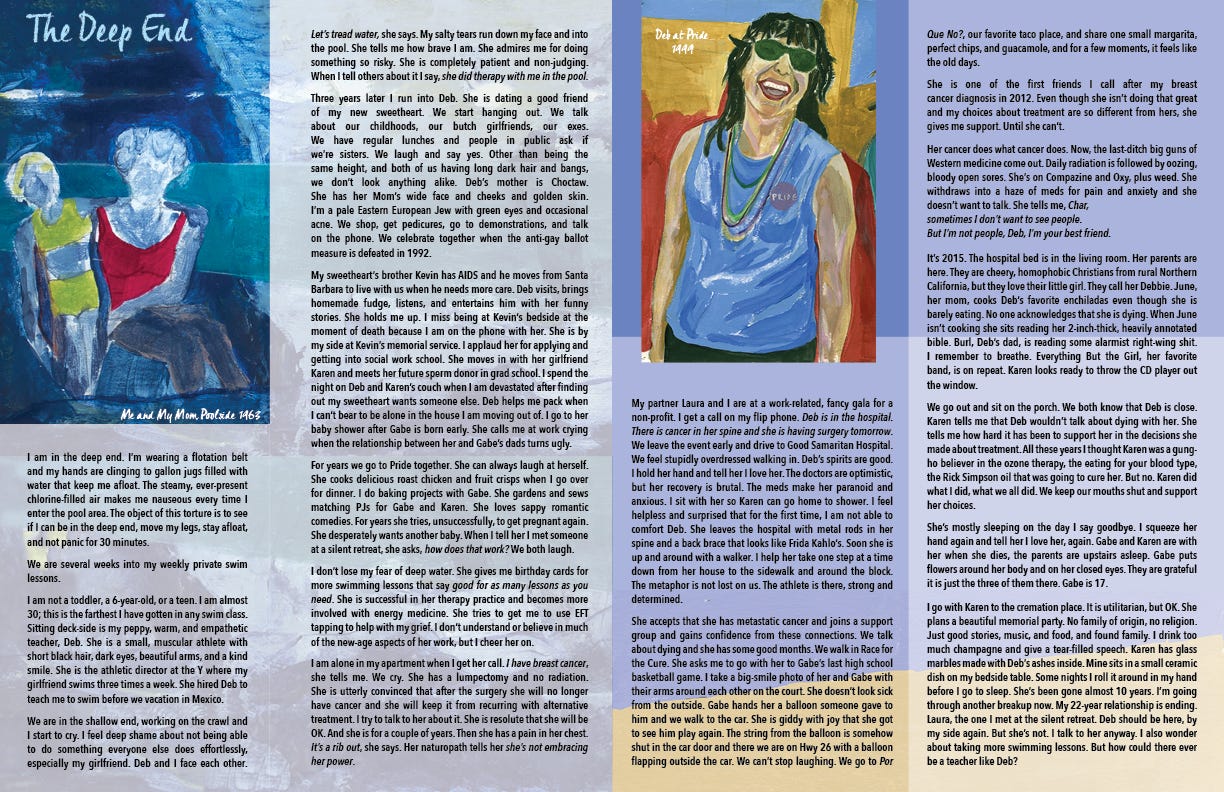

Three years later I run into Deb. She is dating a good friend of my new sweetheart. We start hanging out. We talk about our childhoods, our butch girlfriends, our exes. We have regular lunches and people in public ask if we’re sisters. We laugh and say yes. Other than being the same height, and both of us having long dark hair and bangs, we don’t look anything alike. Deb’s mother is Choctaw. She has her Mom’s wide face and cheeks and golden skin. I’m a pale Eastern European Jew with green eyes and occasional acne. We shop, get pedicures, go to demonstrations, and talk on the phone. We celebrate together when the anti-gay ballot measure is defeated in 1992.

My sweetheart’s brother Kevin has AIDS and he moves from Santa Barbara to live with us when he needs more care. Deb visits, brings homemade fudge, listens, and entertains him with her funny stories. She holds me up. I miss being at Kevin’s bedside at the moment of death because I am on the phone with her. She is by my side at Kevin’s memorial service. I applaud her for applying and getting into social work school. She moves in with her girlfriend Karen and meets her future sperm donor in grad school. I spend the night on Deb and Karen’s couch when I am devastated after finding out my sweetheart wants someone else. Deb helps me pack when I can’t bear to be alone in the house I am moving out of. I go to her baby shower after Gabe is born early. She calls me at work crying when the relationship between her and Gabe’s dads turns ugly. For years we go to Pride together.

She can always laugh at herself. She cooks delicious roast chicken and fruit crisps when I go over for dinner. I do baking projects with Gabe. She gardens and sews matching PJs for Gabe and Karen. She loves sappy romantic comedies. For years she tries, unsuccessfully, to get pregnant again. She desperately wants another baby. When I tell her I met someone at a silent retreat she asks, How does that work? We both laugh.

I don’t lose my fear of deep water. She gives me birthday cards for more swimming lessons that say good for as many lessons as you need. She is successful in her therapy practice and becomes more involved with energy medicine. She tries to get me to use EFT tapping to help with my grief. I don’t understand or believe in much of the new-age aspects of her work, but I cheer her on.

I am alone in my apartment when I get her call. I have breast cancer, she tells me. We cry. She has a lumpectomy and no radiation. She is utterly convinced that after the surgery she will no longer have cancer and she will keep it from recurring with alternative treatment. I try to talk to her about it. She is resolute that she will be OK. And she is for a couple of years. Then she has a pain in her chest. It’s a rib out, she says. Her naturopath tells her she’s not embracing her power.

My partner Laura and I are at a work-related, fancy gala for a non-profit. I get a call on my flip phone. Deb is in the hospital. There is cancer in her spine and she is having surgery tomorrow. We leave the event early and drive to Good Samaritan Hospital. We feel stupidly overdressed walking in. Deb’s spirits are good. I hold her hand and tell her I love her. The doctors are optimistic, but her recovery is brutal. The meds make her paranoid and anxious. I sit with her so Karen can go home to shower. I feel helpless and surprised that for the first time, I am not able to comfort Deb. She leaves the hospital with metal rods in her spine and a back brace that looks like Frida Kahlo’s. Soon she is up and around with a walker. I help her take one step at a time down from her house to the sidewalk and around the block. The metaphor is not lost on us. The athlete is there, strong and determined.

We are in the shallow end working on the crawl and I start to cry. I feel deep shame about not being able to do something everyone else does effortlessly, especially my girlfriend. Deb and I face each other. Let’s tread water, she says.

She accepts that she has metastatic cancer and joins a support group and gains confidence from these connections. We talk about dying and she has some good months. We walk in Race for the Cure. She asks me to go with her to Gabe’s last high school basketball game. I take a big-smile photo of her and Gabe with their arms around each other on the court. She doesn’t look sick from the outside. Gabe hands her a balloon someone gave to him and we walk to the car. She is giddy with joy that she got to see him play again. The string from the balloon is somehow shut in the car door and there we are on Hwy 26 with a balloon flapping outside the car. We can’t stop laughing. We go to Por Que No?, our favorite taco place, and share one small margarita, perfect chips, and guacamole, and for a few moments, it feels like the old days.

She is one of the first friends I call after my breast cancer diagnosis in 2012. Even though she isn’t doing that great and my choices about treatment are so different from hers, she gives me support. Until she can’t.

Her cancer does what cancer does. Now, the last-ditch big guns of Western medicine come out. Daily radiation is followed by oozing, bloody open sores. She’s on Compazine and Oxy, plus weed. She withdraws into a haze of meds for pain and anxiety and she doesn’t want to talk. She tells me, Char, sometimes I don’t want to see people.

But I’m not people, Deb, I’m your best friend.

It’s 2015. The hospital bed is in the living room. Her parents are here. They are cheery, homophobic Christians from rural Northern California, but they love their little girl. They call her Debbie. June, her mom, cooks Deb’s favorite enchiladas even though she is barely eating. No one acknowledges that she is dying. When June isn’t cooking she sits reading her 2-inch-thick, heavily annotated bible. Burl, Deb’s dad, is reading some alarmist right-wing shit. I remember to breathe. Everything But the Girl, her favorite band, is on repeat. Karen looks ready to throw the CD player out the window.

We go out and sit on the porch. We both know that Deb is close. Karen tells me that Deb wouldn’t talk about dying with her. She tells me how hard it has been to support her in the decisions she made about treatment. All these years I thought Karen was a gung-ho believer in the ozone therapy, the eating for your blood type, the Rick Simpson oil that was going to cure her. But no. Karen did what I did, what we all did. We kept our mouths shut and support her choices.

No family of origin, no religion. Just good stories, music, and food, and found family. I drink too much champagne and give a tear-filled speech. Karen has glass marbles made with Deb’s ashes inside. Mine sits in a small ceramic dish on my bedside table. Some nights I roll it around in my hand before I go to sleep.

She’s mostly sleeping on the day I say goodbye. I squeeze her hand again and tell her I love her, again. Gabe and Karen are with her when she dies, the parents are upstairs asleep. Gabe puts flowers around her body and on her closed eyes. They are grateful it is just the three of them there. Gabe is 17.

I go with Karen to the cremation place. It is utilitarian, but OK. She plans a beautiful memorial party. No family of origin, no religion. Just good stories, music, and food, and found family. I drink too much champagne and give a tear-filled speech. Karen has glass marbles made with Deb’s ashes inside. Mine sits in a small ceramic dish on my bedside table. Some nights I roll it around in my hand before I go to sleep. She’s been gone almost 10 years. I’m going through another breakup now. My 22-year relationship is ending. Laura, the one I met at the silent retreat. Deb should be here, by my side again. But she’s not. I talk to her anyway. I also wonder about taking more swimming lessons. But how could there ever be a teacher like Deb?

Char Breshgold has been a working and exhibiting visual artist for 40 years. She paints, often from photos, using her art to tell stories. During the 1980s she was a member of The Girl Artists. A five woman, feminist collaborative group whose archives have recently been acquired by The Smithsonian Archive of American Art. She began creating hybrid flash memoir pieces with words & images 5 years ago and had her first published pieces in Prism, International in 2024. She is at work on a graphic memoir about the AIDS crisis years.

Char, your humor and sensitivity shine through this happy and sad essay. I’m kinda intrigued by how you are a model for how to live through painful times. Thank you for helping us all and creating such a good read.

Beautiful essay. I dropped by via memoir land, and so glad I did!