The Lingering Scent of Black Butter

Ebonya Lia gets caught in Sephora during an earthquake. Metaphorically.

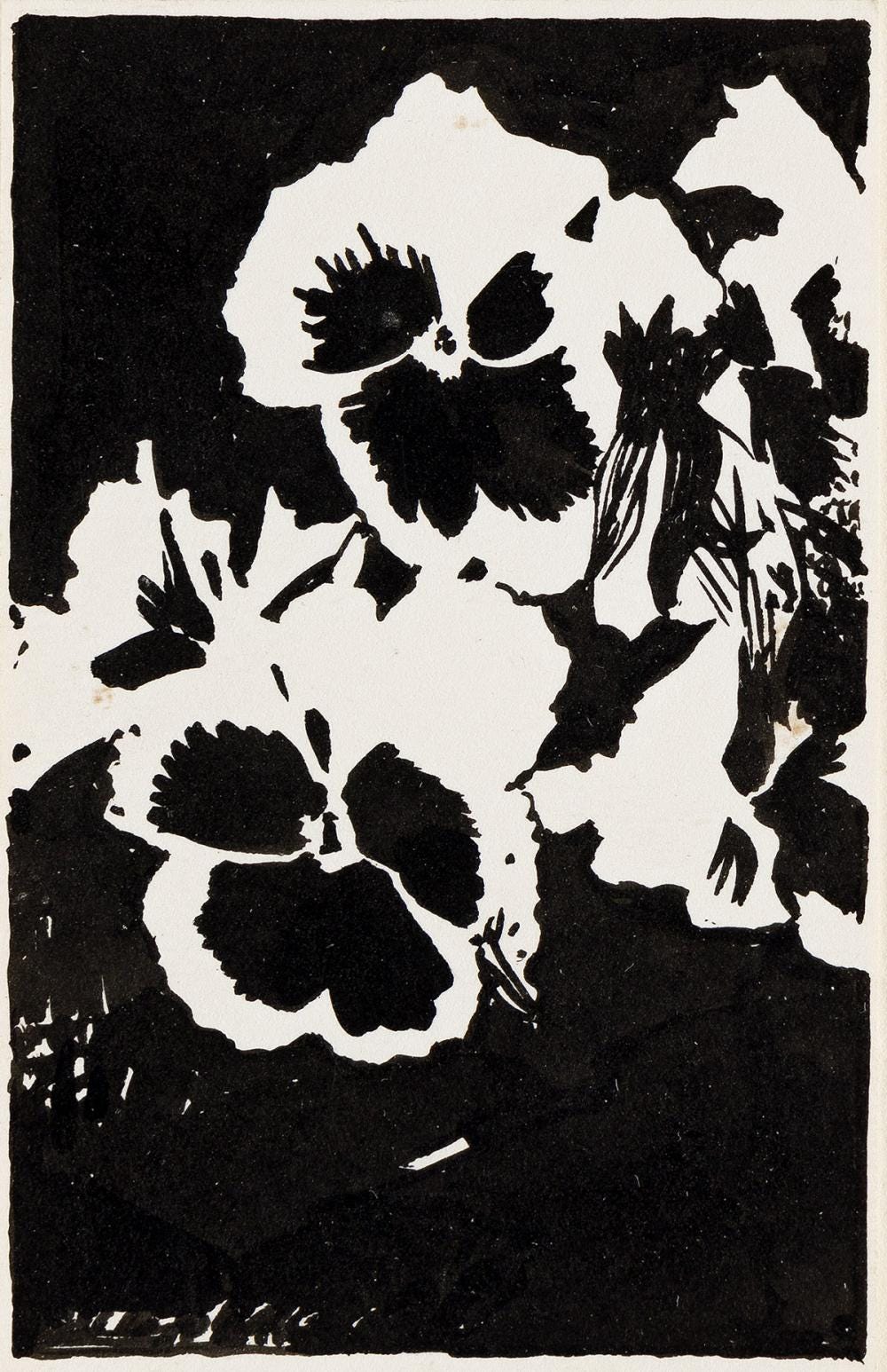

The drawing assignment: Render a person’s likeness without depicting their face. Create a portrait in objects.

My grandmother Choo Choo loved her pocketbooks.

My mother holds onto them.

From the top of her closet, my mother lowers Choo Choo’s everyday bag. It's made of black leather that’s “soft like butter,” in my grandmother’s words. We explore the compartments. My muscles spasm. The wallet bulges with department store credit cards. The oversized sunglasses, an homage to Jackie O. Plastic-wrapped peppermints crinkle in every supple fold.

I might’ve preferred to learn painting. But my illness forbids it. Even the smell of watercolors makes my body react. As does food, clothing, furniture. And most people.

And then there are the clutch bags: the beaded rectangular, the alligator envelope, the black satin clamshell that shuts with a clap. The inside of my throat thickens.

My mother pulls scarves from a metal drawer overhead. My sinuses swell. We recall how Choo Choo knotted the paisley fabrics beneath her chin, like a 1950s movie star.

Inside the compact jewelry box, a confetti of stud earrings. A gold brooch spells out “Mother” with a heart dangling from the word.

My mother unfolds the tissue-thin handkerchief with the Poinsettia pattern. We laugh because we know that this object absolutely must be included in the drawing. Christmas was my grandmother’s favorite day of the year. In the early morning darkness, she’d pull her sleeping daughter out of bed and over to the tree. After I was born, each Christmas Eve I witnessed a tense negotiation that began with my grandmother bidding for a 6 a.m. start to gift-opening and my night-owl mother countering with noon.

I leave my mother’s apartment with a grocery bag full of my grandmother’s possessions. Each swing of my arm shakes up the smell that stokes my body’s rebellion.

I keep walking.

My grandmother is not toxic.

Sure, in her bathroom there were those little soaps with a faint rose scent. On special occasions, it’s true, she dabbed Nina Ricci perfume.

But Choo Choo spoke the words “Ebonya and I” like we were the sole members of the most exclusive club. I felt so proud and safe and loved to hear her boast, “Ebonya and I like that program”, “Ebonya and I want to go to Filenes”, “Ebonya and I are going to pop some sweet potatoes into the microwave for a snack. Does anyone else want anything?”

Sweet potatoes are one of ten foods that I can still eat without provoking symptoms.

My grandmother would never hurt me.

From the top of her closet, my mother lowers Choo Choo’s everyday bag. It’s made of black leather that’s “soft like butter,” in my grandmother’s words. We explore the compartments. My muscles spasm. The wallet bulges with department store credit cards. The oversized sunglasses, an homage to Jackie O. Plastic-wrapped peppermints crinkle in every supple fold.

In my living room, I arrange the objects into a still life for drawing.

I might’ve preferred to learn painting. But my illness forbids it. Even the smell of watercolors makes my body react. As does food, clothing, furniture. And most people.

I itch and fuss, shuffling purses and scarves and jewelry, scrambling scents.

It’s like I’ve sheltered in a Sephora during an earthquake.

My grandmother died ten years before the onset of this unexplained illness that has me smelling smells that no one else smells. Inert smells that power over me.

To fulfill my drawing assignment, I should quickly settle on a composition, snap a photo, and pack these items in the fridge until I can return them to my mother. It’s not like I want to wear the tangerine paisley scarf or carry the handbag sculpted out of black butter.

Yet I’m possessed by a need to fix this. I soak the scarves in a tub of vinegar overnight, although I’ve learned that these tried and true cleansing solutions don’t work for me.

When I lift the scarves from the bath, they smell the same as they did when they went in. I’m not surprised.

I am shattered.

I turn to OxiClean next. Then I pack the fabric in moist baking soda.

And when all that fails, I fall to my knees. I round myself over the tub as the water rushes over the scarves, and suds, and all of those “miracle” cleaners. I plunge the fabric beneath the brine. The water splashes my chest as it leaps up to choke me. I wrestle that fabric down, whip those scarves beneath the tide. Runny-eyed, mucusy, struggling for breath, I pitch my body forward so I can thrust more forcefully. The slats of the wooden bathmat pinch at the center of my knee where the skin is most tender.

I drown the fabrics again, again, again.

Ebonya Lia’s debut novel I Can Feel It All Over on illness, identity, and isolation is forthcoming from Amistad in spring 2027. She lives in Brooklyn with her plant Chris, who is also thankful to finally be under the care of a compassionate doctor. Follow her on IG: @ebonya.lia.

Love the textures and smells through memory and fabric that are evoked in this work. Grandma Choo Choo and her pocket books! I'm smiling.